A Brief Timeline of the Achaemenid Empire

This was actually a term paper of mine for the Anatolian Civilizations in Antiquity I course (HIST 241) but enjoyed working on it a lot, so why not have it here? For the curious, I have here also the original paper and slides.

Table of Contents

- Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Origin

- Cyrus the Great

- Cambyses and Darius’s Accession to the Throne

- Darius the Great

- Greco-Persian Wars and Xerxes

- Artaxerxes I and Darius II

- Artaxerxes II and Artaxerxes III

- Fall of the Persian Empire

- Bibliography

- Classical Sources

- Footnotes

Introduction

We mostly know about the Achaemenid Empire from the perspective of Western History. They were the barbarians1 that waged war on the Greek city states and they were the ones who were defeated and subsequently conquered by the Alexander the Great of Macedon. The Achaemenid Empire was also cherished as they emancipated the Jewish people when they were exiled from Babylon. This is a natural outcome of the fact that we mostly know about the Achaemenids from the secondary sources, most notably Greeks, as Persians left no literary record of their own history2. However, they have a lengthy and illustrious history that deserves being studied from their own perspective.

Origin

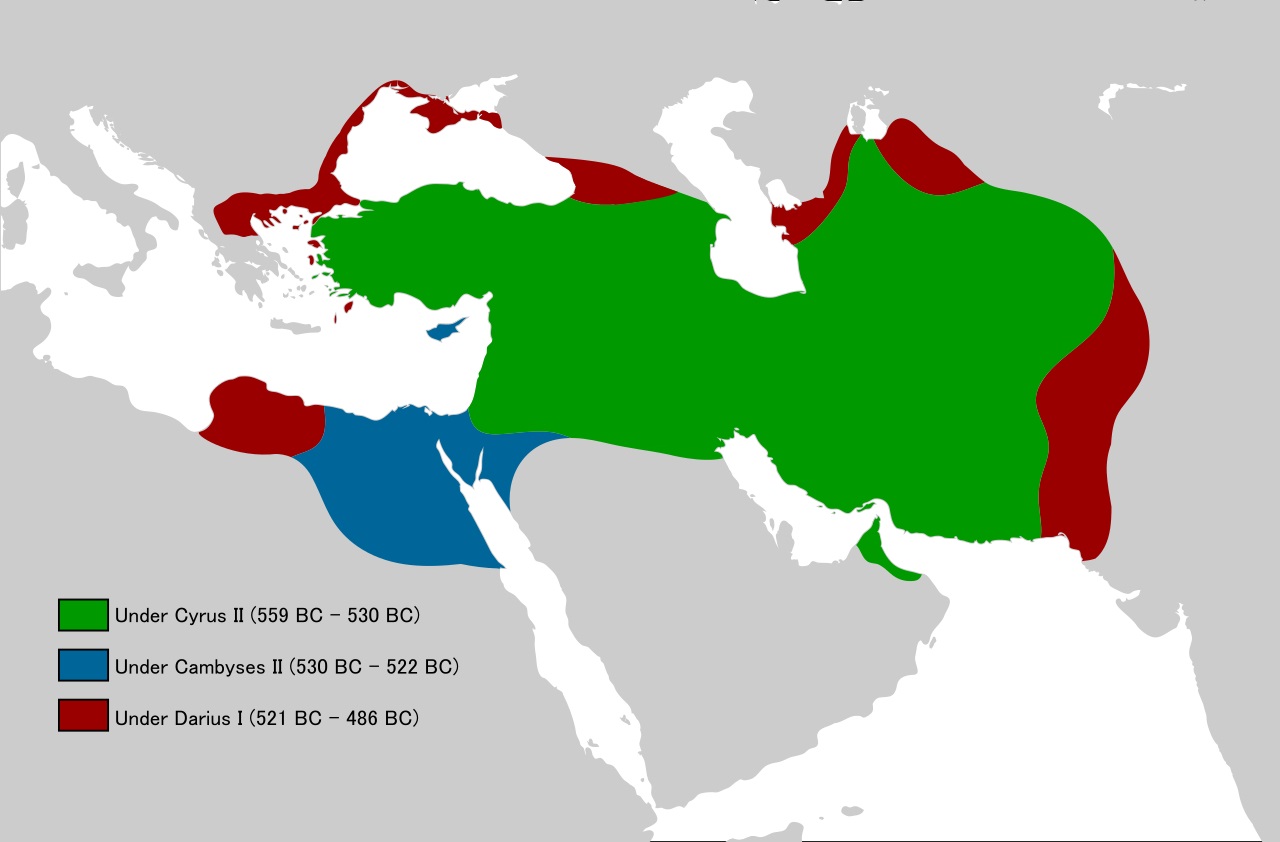

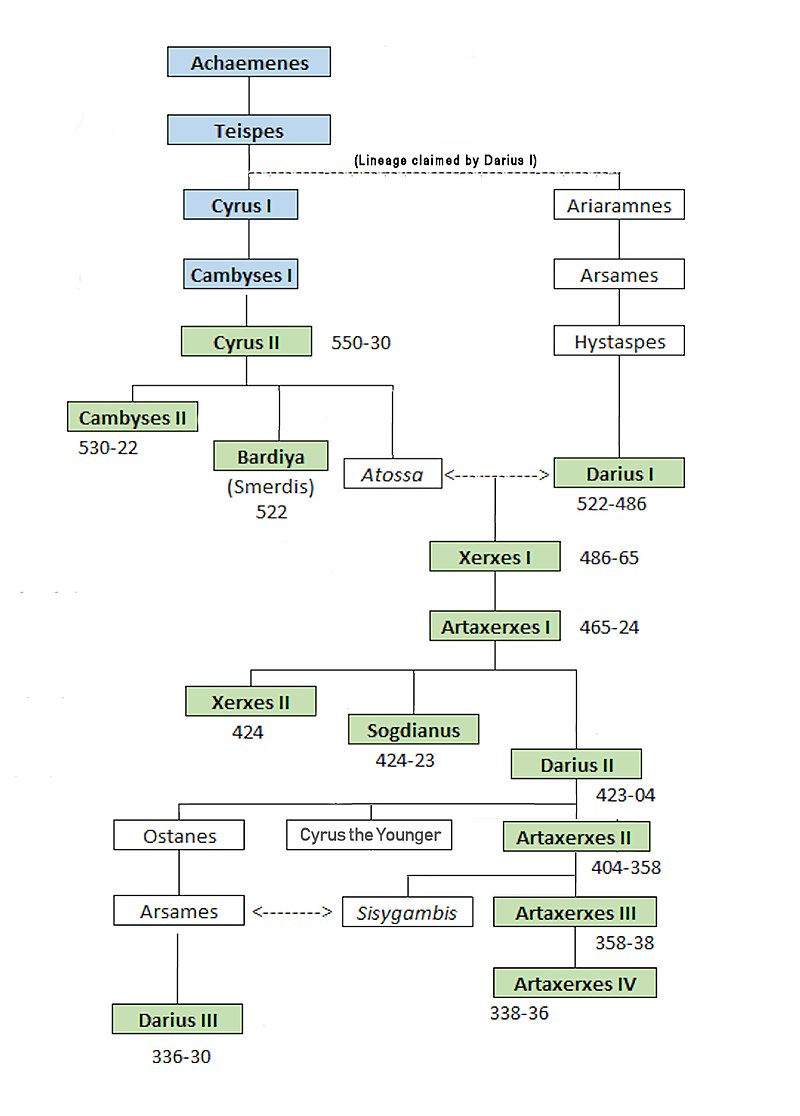

The Achaemenid homeland was Persis (Pārsa in Old Persian), hence the Latin naming of the nomadic tribes as Persians3. It is located in the southwest Iran where the former Elam city of Anshan (Anšan in Old Persian) stood and it now corresponds to the modern province of Fars. The Achaemenid Empire was established around 550 BC by the Cyrus II (Cyrus the Great), but Persians and their kings can be traced back in time to the beginnings of the 7th century BC. First rulers of the Persian kingdom —namely Teispes, Cyrus I and Cambyses I— acted as satraps until the Cyrus the Great’s revolt against the Median Empire.

Achaemenid Empire was the first Persian Empire but they were not the first Iranian Empire. At the time of the Achaemenid Empire’s inception, central Iran belonged to the Medes. Outside the Iranian plateau, the Neo-Babylonian Empire ruled the Mesopotamia in the east, Lydians ruled the Western Anatolia. At the far north there were Scythians and at the southwest, pharaoh Psamtik regained the control of Egypt. Therefore, it can be said political landscape surrounding Persia at the 6th century BC was shaped around the aftermath of the Neo-Assyrian Empire’s collapse and the rise of the Achaemenid Empire could be more easily understood in such historical context, concluding a longue durée4.

Cyrus the Great

To understand the Persians better, we shall look at their leader, and indeed its founder is fairly a good example of how this new empire was viewed both by themselves and from a foreigner’s eye. It could be said with ease that Cyrus the Great earned his epithet by building the largest empire ever existed until his time, merely in his thirty years of reign that began with the very foundations of the same empire. His religious tolerance and humane acts are described in many sources, from Babylonian texts to Biblical ones.

The Achaemenids have been powerful as the kings of Anshan, but they were still under the Median rule. Therefore, Cyrus’s reign starts with the revolt against Astyages, the Median Emperor and coincidentally, his grandfather. Nabonidus Chronicle5 tells us that it was actually Astyages himself, who initially marched against Persians with conquest in mind6. Persians put up a lengthy fight and the tides have turned for them with their last battle near Pasargadae, the Achaemenid capital. Polyaenus describes it as “a victory so complete that Cyrus had no need to fight again”7. This battle was followed with victories against Medes and the war ends as Ecbatana, the Median capital, was captured and Astyages was taken hostage by Cyrus. Cyrus spared Astyages’s life —and even married his daughter Amytis— and he presented himself as the successor of Median Empire8. He then marched on to west and after a series of successive victories in Asia Minor and conquered the Lydian capital Sardis. Cyrus once more acted as merciful to the defeated and spared the Croesus’s life and even received a former Median city. He also appointed a Lydian named Pactyes as the satrap, i.e. local governor, of the Sardis.

These aforementioned deeds are very good examples of the characteristics of Cyrus’s reign, as well as they illustrate the Persian authority in the subsequent periods. As it has been noted before, Cyrus was revered for his respect and tolerance to local customs, autonomy and religions of the lands conquered. Though these policies have been proved to be successful for the Achaemenids the majority of the time, there were exceptional occasions.

Following the conquest of Sardis, Cyrus changed his direction to the east, only to learn the news of a Lydian revolt led by Pactyes. Meanwhile, Ionians and Aeolians were refusing to submit to Achaemenid rule and even seeking help from Sparta against them. Cyrus continued his journey to east but sent back Mazares —the Median general who defected to Cyrus— to Lydia to capture Pactyes and punish the revolting cities, both of which he accomplished successfully. Cyrus directly replaced Pactyes with a Persian named Oroetes, in an effort to balance autonomy and authority9. We don’t know much about Cyrus’s expeditions at that time, but we know that Cyrus captured Babylon in 539.

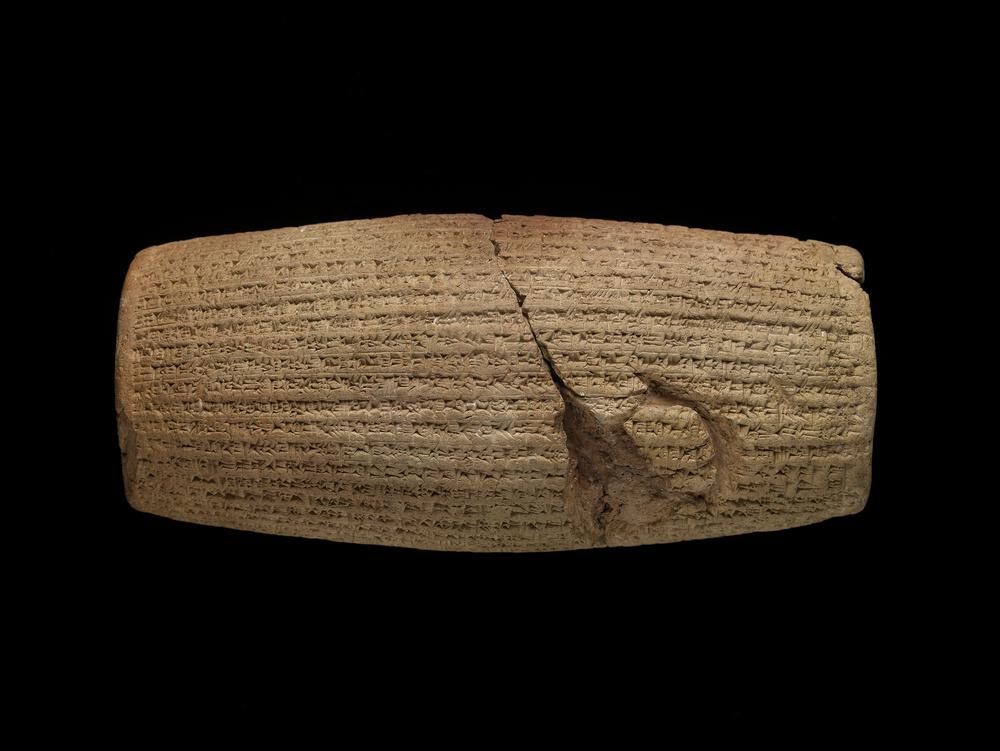

Both the Nabonidus Chronicle and the Cyrus Cylinder10 present us commentary on the Persian conquest of Babylon. The Cylinder tells us how the last king Nabonidus opposed the Babylonian people and their beliefs, as well as it details how the patron deity Marduk favored Cyrus and aided him with his victory. Both sources also take note of how the conquest progressed as peaceful and without a battle. Briant argues that this war in year 539 was probably the last stage of more lengthy hostilities and the Cylinder displays a powerful example in terms of the propaganda and an accompanying political agenda the Persians employ.11 It seems that the Egyptian campaign Cambyses led was in planning stages in the last years of Cyrus’s reign and various sources agree on the point that the Egyptian Pharaoh Amasis deliberately tricked either Cyrus or Cambyses, which can be argued to reflect later Persian propaganda rather than the truth12.

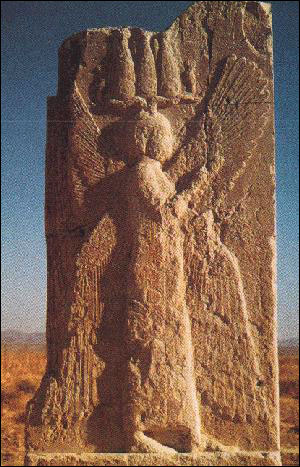

We know that Cyrus died in 530, but accounts of his death vary. His remains were transferred to his capital city of Pasargadae and his tomb is still intact today. In fact, Tomb of Cyrus is a great testimony to the Persian synthesis that happened throughout the Persian rule over two centuries. It exemplifies artistic choices and elements from various cultures, from ones preceded the Persians to ones that came under their rule. Indeed, long before Alexander’s conquests, Achaemenid Empire built a bridge that connected west and the east, ranging from Macedonia in the West to the Indus Valley in the East. Such cultural synthesis is visible in other Persian (as well as Greek) pieces of art. Another example to illustrate the subject could be the painted wooden beams found in a Tatarlı wooden tomb chamber. Summerer details how the painting brings together a multifigured battle composition, common in Eastern Greek art, with traditional Persian iconography.13

Cambyses and Darius’s Accession to the Throne

Cyrus was immediately succeeded by his son Cambyses, as he was appointed as heir by his father. Greek authors Xenophon, Plato and Herodotus compared Cambyses to his father and criticized him as being a decadent and a tyrant, though it would be hard to ascertain such claims with the knowledge of his death and aftermath at hand.14 Cambyses’s successfully followed the path before him and subjugated Egypt after Polycrates of Samos and Phanes of Halicarnassus defected to him. He expanded the Persian borders to the Kushite (modern-day Sudan) territory but had to withdraw his forces after failing in his attempt to invade Nubia. Contrary to the horrendous image of him presented by Classical historians, especially by Herodotus15, Egyptian inscriptions16 17 draw a completely different image of him, portraying Cambyses as a traditional Egyptian ruler.

Cambyses had to leave Egypt and return to his homeland as there was a revolt led by a usurper, in the name of his brother Smerdis18 19, and he died on his way back to Persia after receiving a wound. His death and the events that followed it remain to be one of the most disputed periods of Achaemenid history.

Classical sources —Herodotus in Histories, Ctesias in Persica and Darius I in Behistun Inscription20— detail how Cambyses slew his brother from another mother and kept it as a secret, and that the usurper is a man using his brother’s name to claim right to rule. Modern revisions disagree on this topic with the Classical authors; telling of the story of Bardiya (Smerdis) as presented above and genealogy on Behistun Inscription connecting Darius to Teispes (without mentioning Cyrus, interestingly) can be seen as efforts to legitimate his accession to the Persian throne.21 That way or another, Darius captures and kills Bardiya with the help of six noble Persian families and becomes the third king of the Achaemenid Empire.

Darius the Great

Darius also earned through the test of time the same epithet as his predecessor Cyrus and it is suitable to his exceptional character that is reflected in his works, beginning by his aforementioned accomplishment. During Darius’s reign the Persian Empire lived its golden age. He reorganized the satrapial tribute system, introduced a new currency, standard weights and an official language to the Persian Empire. He expanded the borders, suppressed revolts. He built roads and monuments throughout the empire, palaces in Susa and Persepolis. He even compiled the Egyptian laws and reconstructed temples of Egyptians.

Behistun Inscription boasts about how Darius put down the numerous rebellions that broke out after he became the king.22 We see the measures he has taken to consolidate his power; he executed the rebellious “liar-kings” by first cutting their noses and ears —as it was customary both in Assyrian and Achaemenid period— and then impaling and displaying them publicly.23 We learn from Herodotus that he married Cyrus’s two daughters and his granddaughter through Smerdis.24 On top of this knowledge, how Darius redefined the word Achaemenid and how he proclaimed his authority was from Ahura-Mazda25 marks a new dynastic and imperial order for the Persian Empire.26

Chronological account of Darius’s expeditions after the revolts is disorganized. Herodotus talks about the king’s expeditions to Samos, Egypt, Indus Valley as well as the revolt in Babylon and the campaign against Scythians.27 As Persian borders now run across Thracia, it is of no surprise that there would be encounters with Greeks.

Greco-Persian Wars and Xerxes

One of the most intense periods of Ancient History that still echoes through the Western Culture was kindled by the flame called Ionian Revolt. As it has been discussed before, Ionians were not fond of being under Persian rule, since the conquest of Lydia by Cyrus. Aristagoras was the tyrant of Miletus at that time, preceding his uncle Histiaeus. He wanted to extend his power by conquering Naxos in the name of Persian Empire. Artaphernes, satrap of Sardis and brother of Darius, agreed to lend his forces and Darius has given consent on the plan.

The siege failed as Naxians have managed to fend their island. Artamenes did not see any other option than to rebel and immediately asked Greek city states for help. Sparta refused but Athenians and Eretrians agreed and provided support for the rebellion. They marched on Sardis but Artaphernes effectively defended the citadel and the attackers instead sacked and burned the town. Persian response was swift. Persians under Artaphernes put down the revolt after capturing revolting city states including Miletus. Darius has come to terms with Ionians as he replaced the unpopular tyrants by installing democracy.28 However, he had to punish Athens and Eretria for helping the revolt.

At first, Darius sent his son-in-law Mardonius, who was the son to one of the nobles that helped Darius claim the throne. Though he subjugated Macedonia and Thrace he lost his fleet and had to retreat. Then, Artaphernes —son of the Artaphernes and nephew of Darius— and Datis were appointed for the invasion. The plan was to install a deposed tyrant named Hippias as the ruler of Athens, effectively making it a puppet state. Persians have burned down the Eretria and landed on the Marathon. Though they were considerably outnumbered, Athenians drove out both the land and naval forces of Persians, with the help of the Plataeans. Greeks were not a threat to Persians, per se, but this loss had a significant symbolic importance for Darius as it was a direct insult to his prestige.29 Darius did not live to march against the Greeks once more, but he named an heir before he died and his son led the second invasion of Greece.

After suppressing a revolt in Egypt, Xerxes began the preparations for the invasion. Herodotus writes that the primary action Darius intended and Xerxes executed was not merely punishing Athens but rather conquering the Greeks.30 After several years of preparations at substantial scale31, Xerxes crossed the Hellespont —modern day name for the Dardanelles— and marched against Greeks. Spartans led by their king Leonidas managed to hold and delay the Persian army at the pass at Thermopylae. Persians forces eventually took the pass continued inwards, but an unexpected storm hit the Persian navy. As their defenses fell, Attica and Boeotia were captured and Athens was sacked by the Persians. Meanwhile, Spartans and Athenians put aside their differences and gathered their troops together at the Isthmus of Corinth. Greeks intended to take the advantage of the geography and heavily fortified the narrow straits. Persian navy was lured by Themistocles to Salamis, where Persians suffered a decisive defeat.

Following the Battle of Salamis, Xerxes retreated back to Sardis and ordered his commander Mardonius to continue the offence in Greece. Xerxes then offered Athens peace by declaring that they will leave the state free without installing any tyrant, rebuild the temples destroyed and give them additional land to rule if they come to terms with Persians.32 Contrary to what Spartans genuinely feared, Athenian forces declined the offer twice. After Mardonius marched through Attica, the rivaling forces met at Plataea. Mardonius was killed in battle and it further disheartened the Persian troops which were already suffering a heavy loss. At the same day —or at least soon enough— Persian navy, caught unprepared by the Greek fleet, lost a battle at Mycale.

Later began the Greek offensive and Persians had to fight against the Delian League, a coalition of Greek city-states which also called the Athenian Empire as Athens led them. Greeks defeated the Persian army later at Eurymedon River —modern day Köprüçay, at Antalya— consolidating the Greek defense in the Aegean region. We could say that Greco-Persian Wars resulted in a territorial loss as Persians lost numerous Aegean islands and their grasp on Thrace. It would be also fair to argue that the Babylonian Revolt and the Second Ionian Revolt were influenced by the recent Persian defeats, Persian army was still strong and we would not say the Persian king lost his influence or his prestige.33

Artaxerxes I and Darius II

Xerxes was then assassinated and the Greek sources on this plot —Ctesias, Justin and Diodorus— agree on a broad picture, though they contradict on many points.34 Artabanus, a high ranked official and commander of the royal bodyguard according to Diodorus, assassinates the king in his bedroom. He gets help from his sons (Justin), a eunuch named Aspamithres (Ctesias) or Xerxes’s chamberman Mithradates (Diodorus). Conspirators convince the youngest son Artaxerxes that his oldest brother killed his father. Artaxerxes then kills Darius and becomes the new king.

Artaxerxes I faced the Egyptian revolt led by a Libyan prince named Inarus, which was supported by the Athenian navy. The revolt was crushed and Inarus was executed, but Persians kept his son in power. Combined with more attentiveness in Egypt’s militaristic affairs, this strategy of keeping a dynasty in power proved useful, at least in Artaxerxes’s reign in which Egypt remained peaceful. As their attempt to conquer Cyprus, Athenians began talking peace with Persians, which resulted in so-called Peace of Callias. Although the state of war has been ceased, Persians saw opportunities in the western front. Tension was rising between Sparta and Athens —which will eventually present itself in Peloponnesian Wars— and Persians interfered through ambassadors and bribery in the Greek affairs. It is also an interesting turn of events that Themistocles, the Greek general of Salamis, was exiled and seeking refuge. Artaxerxes welcomed him and granted him the revenues of some small Asian towns.

Artaxerxes died after enjoying a long reign lasted from 465 to 424 and his only legitimate son was crowned king as Xerxes II. Ctesias writes in Persica his reign only lasted for 45 days as he was assassinated and replaced by Sogdianus, his illegitimate brother born to Alogyne. Likewise, Sogdianus did not enjoy the title for too long either. His brother Ochus, born to Cosmarditene, claimed the throne under the regnal name of Darius II. His brother Arsites from same mother and Artyphius, son of Megabyzus, both rebelled against the new king with no avail; they were captured and put to death.35

After suppressing a Median revolt, Darius II renewed the truce between Persia and Athens, although Athenians supported a revolt in Sardis only a few years effectively violating the truce. At that time, Greek city-states led by Sparta and Athens were in war. As Athenians failed at conquering Peloponnesian controlled Sicily, Darius saw the advantage and formed an alliance with Spartans. Darius bestowed upon his younger son Cyrus power and money and sent him to western front to control the Greek situation.36 He solved the inter-satrapal rivalry in Asian Minor and formed personal relations with the Spartan general Lysander, even leaving him large sums of money as Cyrus was sent for his father in deathbed.37 As sources on him were scarce, we do not know about his reign on other parts of the empire.

Artaxerxes II and Artaxerxes III

After Darius’s death, his oldest son Arses was crowned king as Artaxerxes in Pasargadae. Parysatis was the mother of both Cyrus and Artaxerxes and it is told that she favored her younger, Cyrus, over Arses.38 (She also went on to poison Artaxerxes’s wife Stateira39) Sources tell us40 ambitious Cyrus returned to Sardis and began preparations. It is likely that Artaxerxes was suspicious, if not informed, of these events but he was both occupied with Egyptians and rather unworried as his influence in Asia Minor acted as deterrent against Cyrus. Cyrus amassed troops in west, most notably Greek mercenaries titled later as The Ten Thousand —oi Myrioi— and began marching on Babylonia.41 At the Battle of Cunaxa, however, Cyrus was killed and Artaxerxes was proven victor.42

Artaxerxes then fought against Spartans led by Agesilaus II. He supported and bribed other Greek city-states —Athens, Argos, Corinth and Thebes— against Spartans, effectively igniting the flame for Corinthian War. Subsequently, he also crushed the Great Satraps’ Revolt. He enjoyed a reign of 46 years, longest in the history of the Achaemenids. After his death, Ochus was crowned king as Artaxerxes III, as his brothers preceding him in the line of succession were executed, killed or committed suicide.

Immediately following the accession, Artaxerxes dealt with the rebellion of Artabazus, the satrap of Phrygia —initially supported by Athens and after the treaty with them, by Thebes. He suppressed the revolt and Artabazus took up exile in Macedonia. He then wanted to reclaim Egypt for the empire, which was ruled at that time by Pharaoh Nectanebo II. He failed to do so in his attempt in year 351, but after contingents from Greek city-states and Mentor of Rhodes joined his army, he conquered Egypt in 342-342. Because of the actions he took, he is oftentimes compared to Cambyses in both Ancient and Classical texts —even accused of killing the sacred bull of Apis just like Cambyses.43

Fall of the Persian Empire

Artaxerxes III was poisoned in his court by the Bagoas, who was the vizier at that time and he was holding immense power by the end of the Artaxerxes’s reign.44 Diodorus continues with telling us that Bagoas also had all of the deceased king’s sons murdered except Arses, who ruled two years as Artaxerxes IV. Arses finally began contemplating eliminating Bagoas and therefore killed by him, likewise his father. Bagoas then selected Darius, a cousin of Arses, for the throne. Story goes on with Bagoas trying to poison Darius III as he was getting out of his grasp, but Darius making him to drink the poison, which can be viewed as a later propaganda.45 46

Macedonian offensive began with the Battle of Chaeronea. Philip II of Macedon defeated the Greek city-states —not including Sparta— and formed the League of Corinth under his leadership. A twenty years old Alexander succeded the throne after his father was assassinated. He subdued the neigboring states, reassembled the League (most notably destroying Thebes as punishment) and began marching towards Anatolia to fulfill his father’s dream of invading Persia.47

He crossed the Hellespont and won his first victory against the Persians at the Battle of Granicus. One and a half year later, Darius faced the Macedonian army at Issus. Despite outnumbering Alexander’s forces, Persian army was outflanked and defeated. Darius fled, leaving behind his family and his headquarters. Alexander continued his campaign by capturing Tyre after they refused to surrender, then subsequently taking over Gaza and Egypt. Even after the battle at Issus, Darius had the upper hand in numbers —although equipped poorly— and Alexander was nervous about the siege of Babylon.48 Two armies faced each after two years at Gaugamela. Defeated once more, Darius retracted to Ecbatana to raise an army again, knowing that the Alexander’s army would head towards Babylon. Alexander continued his advancements towards east. Through successful maneuvers and defections of Mazaeus, Abulites and Tiridates, Alexander captured Susa, Babylon, Persepolis and Pasargadae. He was still chasing Darius in Median territory when Bessus, the Bactrian satrap at that time, betrayed and assassinated him —he had lost his authority after recent political and military failures.49

Darius III was gone, but until Alexander’s demise, the Great Empire lived. Briant gives an overall conclusion of the Empire’s fate.50 Alexander the Great was a foreigner to East, nevertheless, and he mostly kept the already working satrapal systems along with local rulers. His intention could be seen as creating a homogeneous state, but even in his lifetime there were cracks in his newly build empire; same problems existed before continued to exist in similar nature. Alexander’s reign can be seen as a continuation of the Achaemenid rule, as not much changed from a local’s perspective except a shift in the power of the ruling class. “The last of the Achaemenids” died in 323 BC and his great empire divided among his generals —Diadochi—, marking the beginning of the Hellenistic period.

Bibliography

- Briant, Pierre. From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire, trans. Peter T. Daniels, Winona Lake, IN, Eisenbraun, 2002

- Dusinberre, Elspeth R. M. Empire, authority, and autonomy in Achaemenid Anatolia, Cambridge, NY, Cambridge University Press, 2013

- Lloyd, Alan B. “The Inscription of Udjaḥorresnet a Collaborator’s Testament”, The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 68, Sage, 1982

- Martin, Thomas R. Ancient Greece: From Prehistoric to Hellenistic Times, Second Edition, Yale University Press, 2013

- Posener Georgus. “Les douanes de la Méditerraneé dans l’ Égypte saïte.”, Revue de philologie 21, 1947

- Summerer, Latife. “Picturing Persian Victory: The Painted Battle Scene on the Munich Wood”, Achaemenid Culture and Local traditions in Anatolia, Southern Caucasus and Iran: New Discoveries, Leiden, Brill, 2007

Classical Sources

- Diodorus, Bibliotheca historica, XVI.50.8, XVII.5.4-6

- Herodotus, Histories, III.25-38, III.62-65, III.88, VII.138, VII.20-37

- Plutarchos, Artaxerxes, 2.3-4, 5-6

- Polyaenus, Stratagems of War VII.6.9

- Xenophon, Hellenica, 1.4.3

- Xenophon, Anabasis, I.2-4

Footnotes

-

Although in ancient Greek the term βάρβαρος is commonly used for all the non-Greek peoples, it is mostly used for referring to Persians in the years of Greco-Persian wars. ↩

-

Pierre Briant, From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire, trans. Peter T. Daniels (Winona Lake, IN, Eisenbraun, 2002), 16 ↩

-

These same people will be referred to as both Persians and Achaemenids through the rest of the paper. ↩

-

Briant, From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire, 13 ↩

-

An ancient Babylonian text that narrates the time period from the reign of last Babylonian king to the reign of Cambyses II, Cyrus’s son and successor. ↩

-

Nabonidus Chronicle II. 1-4 ↩

-

Polyaenus, Stratagems of War, VII.6.9 ↩

-

Briant, From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire, 33 ↩

-

Elspeth R. M. Dusinberre, Empire, authority, and autonomy in Achaemenid Anatolia, (Cambridge, NY, Cambridge University Press, 2013), 43 ↩

-

A foundation deposit from the conquest of Babylon, written in Akkadian cuneiform ↩

-

Briant, From Cyrus to Alexander: Ahistory of the Persian Empire, 43 ↩

-

Briant, From Cyrus to Alexander: Ahistory of the Persian Empire, 49 ↩

-

Latife Summerer, “Picturing Persian Victory: The Painted Battle Scene on the Munich Wood”, Achaemenid Culture and Local traditions in Anatolia, Southern Caucasus and Iran: New Discoveries, (Leiden, Brill, 2007): 6-7 ↩

-

Briant, From Cyrus to Alexander: Ahistory of the Persian Empire, 50 ↩

-

Herodotus, Histories III 25-38 ↩

-

Georgus Posener, “Les douanes de la Méditerraneé dans l’ Égypte saïte.”, Revue de philologie 21, (1947): 117-31 ↩

-

Alan B. Lloyd, “The Inscription of Udjaḥorresnet a Collaborator’s Testament”, The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 68, (Sage, 1982): 166-180 ↩

-

Herodotus, Histories III 62-65 ↩

-

This same person is called as Smerdis (Smerdies), Sphendadates, Bardiya (Pirtiya, Barziya), Gaumāta, Tonyoxarces (Tanooxares) and Mardos (Mergis) through various sources. ↩

-

A rock relief authored by Darius I that took named after its location at Mount Behistun. It contains the translations of the same text in three languages (Old Persian, Elamite and Babylonian, all in cuneiform script) and it has been the key to deciphering cuneiform. ↩

-

Briant, From Cyrus to Alexander: Ahistory of the Persian Empire, 97-111 ↩

-

Behistun Inscription, throughout all the five columns. Translation is presented as follows: Leonard William King, Thompson Reginald Campbell, The sculptures and inscription of Darius the Great on the Rock of Behistûn in Persia : a new collation of the Persian, Susian and Babylonian texts, (London, Longmans, 1907) ↩

-

Briant, From Cyrus to Alexander: Ahistory of the Persian Empire, 123 ↩

-

Herodotus, Histories, III.88 ↩

-

Name given to the God of the Zoroastrianist faith. Darius can be seen through his inscriptions as a devout follower of Zoroastrianism. ↩

-

Briant, From Cyrus to Alexander: Ahistory of the Persian Empire, 138 ↩

-

Briant, From Cyrus to Alexander: Ahistory of the Persian Empire, 140-146 ↩

-

Thomas R. Martin, Ancient Greece: From Prehistoric to Hellenistic Times, Second Edition, (Yale University Press, 2013), 127-128 ↩

-

Thomas R. Martin, Ancient Greece: From Prehistoric to Hellenistic Times, Second Edition, 129 ↩

-

Herodotus, Histories, VII.138 ↩

-

Herodotus, Histories, VII.20-37 ↩

-

Thomas R. Martin, Ancient Greece: From Prehistoric to Hellenistic Times, Second Edition, 134-135 ↩

-

Briant, From Cyrus to Alexander: Ahistory of the Persian Empire, 540-542 ↩

-

Briant, From Cyrus to Alexander: Ahistory of the Persian Empire, 563-564 ↩

-

Briant, From Cyrus to Alexander: Ahistory of the Persian Empire, 589 ↩

-

Xenophon, Hellenica, 1.4.3 ↩

-

Briant, From Cyrus to Alexander: Ahistory of the Persian Empire, 600 ↩

-

Plutarchos, Artaxerxes, 2.3-4 ↩

-

Plutarchos, Artaxerxes, 5-6 ↩

-

Briant, From Cyrus to Alexander: Ahistory of the Persian Empire, 616-620 ↩

-

Xenophon, Anabasis, I.2-4 ↩

-

Briant, From Cyrus to Alexander: Ahistory of the Persian Empire, 621-630 ↩

-

Briant, From Cyrus to Alexander: Ahistory of the Persian Empire, 687-688 ↩

-

Diodorus, Bibliotheca historica, XVI.50.8 ↩

-

Diodorus, Bibliotheca historica, XVII.5.4-6 ↩

-

Briant, From Cyrus to Alexander: Ahistory of the Persian Empire, 777 ↩

-

Thomas R. Martin, Ancient Greece: From Prehistoric to Hellenistic Times, Second Edition, 243-245 ↩

-

Briant, From Cyrus to Alexander: Ahistory of the Persian Empire, 842 ↩

-

Briant, From Cyrus to Alexander: Ahistory of the Persian Empire, 865 ↩

-

Briant, From Cyrus to Alexander: Ahistory of the Persian Empire, 873-876 ↩